More than One Way to Kill a Spruce Forest: The Role of Fire and Climate in the Late-Glacial Termination of Spruce Woodlands across the Southern Great Lakes

Abstract

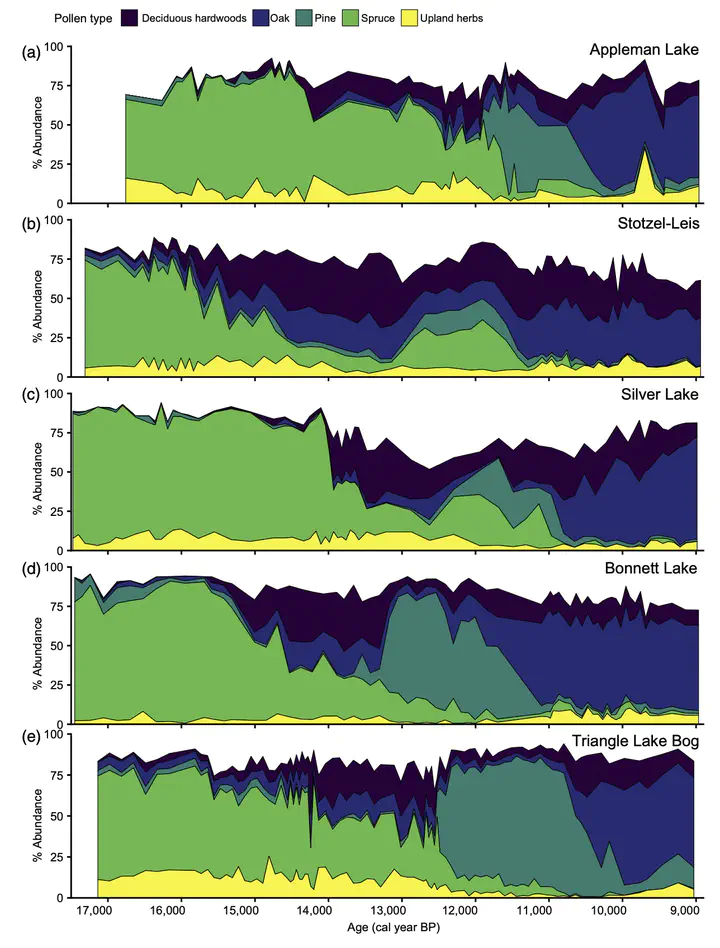

In the southern Great Lakes Region, North America, between 19,000 and 8,000 years ago, temperatures rose by 2.5-6.5 degrees C and spruce Picea forests/woodlands were replaced by mixed-deciduous or pine Pinus forests. The demise of Picea forests/woodlands during the last deglaciation offers a model system for studying how changing climate and disturbance regimes interact to trigger declines of dominant species and vegetation-type conversions. The role of rising temperatures in driving the regional demise of Picea forests/woodlands is widely accepted, but the role of fire is poorly understood. We studied the effect of changing fire activity on Picea declines and rates of vegetation composition change using fossil pollen and macroscopic charcoal from five high-resolution lake sediment records. The decline of Picea forests/woodlands followed two distinct patterns. At two sites (Stotzel-Leis and Silver Lake), fire activity reached maximum levels during the declines and both charcoal accumulation rates and fire frequency were significantly and positively associated with vegetation composition change rates. At these sites, Picea declined to low levels by 14 kyr BP and was largely replaced by deciduous hardwood taxa like ash Fraxinus, hop-hornbeam/hornbeam Ostrya/Carpinus and elm Ulmus. However, this ecosystem transition was reversible, as Picea re-established at lower abundances during the Younger Dryas. At the other three sites, there was no statistical relationship between charcoal accumulation and vegetation composition change rates, though fire frequency was a significant predictor of rates of vegetation change at Appleman Lake and Triangle Lake Bog. At these sites, Picea declined gradually over several thousand years, was replaced by deciduous hardwoods and high levels of Pinus and did not re-establish during the Younger Dryas. Synthesis. Fire does not appear to have been necessary for the climate-driven loss of Picea woodlands during the last deglaciation, but increased fire frequency accelerated the decline of Picea in some areas by clearing the way for thermophilous deciduous hardwood taxa. Hence, warming and intensified fire regimes likely interacted in the past to cause abrupt losses of coniferous forests and could again in the coming decades.